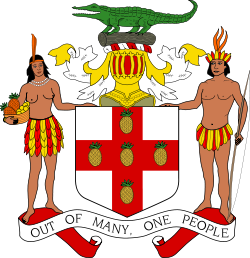

Piloting Natural Resource Valuation within Environmental Impact Assessments in Jamaica

Project Overview

The objective of this project was to develop a set of natural resource valuation tools, and incorporate these into policies and procedures governing the preparation and use of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). The project sought to demonstrate the use of these techniques to improve the decision-making process concerning economic development projects that may potentially affect the environment. The project employed a strategy of targeted capacity development activities to develop a set of natural resource valuation tools that are particular to the Jamaican context, and provided training on the use of these tools.

Project Details

Project Brief:

This project will strengthen the implementation of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA), as well as contribute to the implementation of Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) through the development and application of natural resource valuation tools. In particular, the project will work in parallel with the Environmental Action Programme (ENACT), as SEAs are undertaken on various sectoral policies, programmes and plans. The project will ‘top-up’ ENACT’s capacity development activities of training and sensitization of the value of SEAs, and enforcement and compliance of EIAs with training and sensitization on the utility of natural resource valuation as a means to meeting both national and global environmental objectives over the long-term.

The development of natural resource valuation tools will provide an opportunity for these to be institutionalized as part of ENACT Programme’s capacity development activities. In this way, SEAs will be greatly improved in being able to make better predictions of possible consequences of policy interventions, facilitating the development of strategies to reduce policy resistances and facilitate the consideration of environmental risks and impacts associated with the implementation of government policies. By providing a more robust and comparable valuation method for natural resources, consequences of development policies, programmes and plans will be better evaluated so as to promote biodiversity conservation; minimize, if not reduce the risks associated with land degradation; encourage climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies; and promote environmentally sound and sustainable development

The Government of Jamaica will execute this project over a period of three years, starting in 2008 with the National Environment and Planning Agency as the main implementing partner, working closely with a Project Steering Committee (PSC) that will provide high-level policy guidance and oversight. A project management unit will execute the project. The total budget of the project is US$ 555,250 of which US$ 470,000 is from the GEF. The UNDP is the GEF Implementing Agency.

Part 1: Situation Analysis

Jamaica’s ecosystems provide invaluable services, such as shoreline protection; sinks for pollutants; nursery for juvenile fish; habitats for endangered, threatened, rare and endemic species; and provision of food, shelter and other valuable functions and services. Ecosystem functions help to reduce the impacts of natural disasters, such as storms and hurricanes with associated storm surge, wave action and high wind velocities. In particular, naturally occurring mangroves and reefs provide critical buffers from storm surges associated with hurricanes. Forested ground cover also allows for greater water absorption and retention, reducing the risk of flash floods associated with heavy rainfall events.

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) are part of the requirements under the Permit and License System (1991) administered by the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA). However, the EIA process has a number of weaknesses, including a lack of clear standards and methodologies required for EIA data collection; inadequate tools for the identification of significant impacts; and inadequate specification of impact mitigation measures and environmental management plans. Additionally, some development projects are not included in the EIA process, both by the government and the private sector.

Guidelines for conducting Environmental Impact Assessments were originally prepared in July 1997 and revised in April 2005.The ENACT Programme set out “to develop the capacity of key strategic players at the government policy, private sector, community and general public levels to identify and solve their environmental problems in a sustainable way.” Among the achievements of the ENACT Programme is the strengthening of NEPA in terms of a more hands-on technical development and review of various environmental guidelines and regulation, which includes the EIA approval process. A manual for the review and generic terms of references for the implementation of EIAs was also developed.

Notwithstanding these improvements in capacities, the EIA remains a tool that does not adequately convey the value of ecosystem functions. In reviewing the environmental impacts of a proposed development, the EIA builds on available scientific knowledge to make certain predictions about the possible extent of environmental impact. However, natural resources and ecosystem functions and services are not assigned a monetary value. This makes it virtually impossible to compare the financial values of the development, and the opportunity costs of possible environmental impacts. Standard financial management practices are inherently perverse when it comes to valuing environmental goods and services. For example, clean water is free until there is a cost associated with the provision of potable water supply, and then this cost does not include indirect values, such as the quality of water needed to maintain healthy ecosystems with no direct economic value assigned.

The relevant GoJ agencies (e.g., NEPA, FD, WRA) are particularly constrained in undertaking economic and financial assessments of the natural resource values under their jurisdiction, as these are not skills generally called for within these types of technical agencies. The institutional linkages with agencies that may be capable of doing this are weak, limited to cooperation in terms of the financial and economic assessments of socio-economic development priorities, and not determining non-use values.

To better direct efforts to implement national policies and legislation, the GoJ adopted the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in December 2005 as a tool for assessing the environmental implication of proposed development policies, programmes and plans, with the aim of environmental protection. Implementation of the SEA is intended to facilitate a change in the attitudes towards environmental protection and policy coordination, strengthening the rigor of the policy-making process, and increasing the accountability of governmental official for the environmental implications of their policy decisions. The GoJ, with financial support from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), and executed by the Environmental Action1 (ENACT) Programme initiated the development of guidelines for the implementation of the SEA in early 2006.

PART II: Strategy

The maintenance of Jamaica’s natural resources and environmental services also has real values and costs in socio-economic terms. Water supply, for example, is an important environmental good and service with very real socio-economic value and cost. Over 30% of Jamaica’s freshwater supply is stored in the aquifer maintained by the forest cover of the Cockpit Country, representing a real value in terms of freshwater supply for potable water and irrigation. The potential loss or diminution of this water supply will have real economic costs in terms of reduced water flows in streams and tributaries, resulting in land degradation, increased risk of destroying the sensitive shrimp industry downstream, as well as high opportunity costs such as the loss of endemic species with a potentially high value to the pharmaceutical industry.

Maintaining these natural resource values are difficult given the national priority of socio- economic development and Jamaica’s institutional framework governing natural resource use and environmental management, which is heavily biased against protection in favour of extraction and exploitation for short-term economic gains. In this respect, the GoJ has institutionalized a number of institutional responses. The first of these is the use of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), which serve as the main decision-making tool for the government to manage development in a way that does not seriously undermine the natural resource base, including the loss of biodiversity, land degradation and pollution.

The capital budgeting of development projects are evaluated using different approaches, selected by the project proponent to skew reported returns (a low rate of return if management wants the project to look less worthwhile, or an inflated rate of return if the proponent has a personal preference for the project). The theory behind attaching economic value and cost associated with the ecosystem functions (e.g., clean air, freshwater, fertile soil and stable landscapes), is that decisions will be based on a more complete understanding of the full cost (i.e., the socio-economic opportunity cost) of development that alters the environment, directly or indirectly. For example, the cost of damage from past hurricanes would be reflected as an economic value associated with the protection of barrier reefs and mangroves, among others. Similarly, the cost of economic damage due to flooding and landslides is an economic value of maintaining adequate forest ground cover upstream.

By attaching financial and economic value to ecosystem functions and services, EIAs would allow for a more accurate representation of the costs associated with development.

Of global importance, the project will develop and demonstrate capacities (in the form of natural resource valuation tools) and the use thereof to meeting international commitments with respect to the CBD, CCD and FCCC. Article 4(1)(f) of the FCCC, Article 14 of the CBD, and Article 17(1)(a) of the CCD all call for the use and improvements of the EIA to minimize adverse environmental impacts of development programmes and projects.

Project Objective Statement: The objective of this project is to develop a set of natural resource valuation tools, and incorporate these into policies and procedures governing the preparation and use of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). The project will demonstrate the use of these techniques to improve the decision-making process concerning economic development projects that may potentially affect the environment. The project will employ a strategy of targeted capacity development activities to develop a set of natural resource valuation tools that are particular to the Jamaican context, and provide training on the use of these tools3.

Project Outcome: At the end of the project, the Government of Jamaica will be better able to make more informed decisions by placing greater value to ecosystem functions within the framework of environmental impact assessments of development projects. Specifically, the environmental impacts of all major development projects would be assessed in terms of their financial and economic values, which would be used to make more informed decisions and choices about future development.

Source: Jamaica Project Document - Piloting Natural Resource Valuation within Environmental Impact Assessments (

Key Results and Outputs

Goal: To strengthen the review and approval processes of development projects in order to catalyze environmentally sound and sustainable development.

Outcome 1: Natural resource valuation tools developed

- Output 1.1: A primer/sourcebook on tools and techniques for the use of natural resource valuation specific to the Jamaican context developed

- Output 1.2: Guidelines developed for the application of natural resource valuation tools and techniques within the EIA process

- Output 1.3: Development of actuarial products initiated

- Output 1.4: Independent expert analysis of natural resource valuation tools confirms their high scholarship

- Output 1.5: An implementation plan developed for undertaking natural resource valuation tools within the framework of EIAs

Outcome 2: Natural resource valuation tools piloted within the framework of an EIA

- Output 2.1: Pilot EIA project proposal that integrates the use of natural resource valuation developed and approved

- Output 2.2: Independent evaluation of the pilot EIA project conducted

- Output 2.3: Lessons learned from pilot project are widely disseminated

- Output 2.4: Recommendations for the development SEA implementation guidelines provided

- Output 2.5: Actuarial products developed in Output 1.1 are tested in pilot EIA project.

Outcome 3: Capacities strengthened to use natural resource valuation within the framework of their review and approval processea

- Output 3.1: Curriculum on natural resource valuation developed and incorporated as a course offering in MIND.

- Output 3.2: Natural resource valuation curriculum integrated into course offerings of other academic institutions of higher learning

- Output 3.3: NEP A staff and members of the NRCA Advisory Board and TRC responsible for reviewing proposed developments are trained on interpreting natural resource valuation data and information

- Output 3.4: NGOs involved in community-based development actively participated in sensitization workshops on valuation tools.

- Output 3.5: Media outlets publish regular accounts of the issues concerning developments, subjected to EIAs, with particular reference to the opportunity costs of natural resource and environmental degradation.

Outcome 4: Lessons learned publication widely disseminated

Reports and Publications

ProDocs

Piloting Natural Resource Valuation within Environmental Impact Assessments in Jamaica - Project Document (2007)

Monitoring and Evaluation

- Project Start:

- Project Inception Workshop: will be held within the first 2 months of project start with those with assigned roles in the project organization structure, UNDP country office and where appropriate/feasible regional technical policy and programme advisors as well as other stakeholders. The Inception Workshop is crucial to building ownership for the project results and to plan the first year annual work plan.

- Daily:

- Day to day monitoring of implementation progress: will be the responsibility of the Project Manager, based on the project's Annual Work Plan and its indicators, with overall guidance from the Project Director. The Project Team will inform the UNDP-CO of any delays or difficulties faced during implementation so that the appropriate support or corrective measures can be adopted in a timely and remedial fashion.

- Quarterly:

- Project Progress Reports (PPR): quarterly reports will be assembled based on the information recorded and monitored in the UNDP Enhanced Results Based Management Platform. Risk analysis will be logged and regularly updated in ATLAS.

- Annually:

- Annual Project Review/Project Implementation Reports (APR/PIR): This key report is prepared to monitor progress made since project start and in particular for the previous reporting period (30 June to 1 July). The APR/PIR combines both UNDP and GEF reporting requirements.

- Periodic Monitoring through Site Visits:

- UNDP CO and the UNDP RCU will conduct visits to project sites based on the agreed schedule in the project's Inception Report/Annual Work Plan to assess first hand project progress. Other members of the Project Board may also join these visits. A Field Visit Report/BTOR will be prepared by the CO and UNDP RCU and will be circulated no less than one month after the visit to the project team and Project Board members.

- Mid-Term of Project Cycle:

- Mid-Term Evaluation: will determine progress being made toward the achievement of outcomes and will identify course correction if needed. It will focus on the effectiveness, efficiency and timeliness of project implementation; will highlight issues requiring decisions and actions; and will present initial lessons learned about project design, implementation and management. Findings of this review will be incorporated as recommendations for enhanced implementation during the final half of the project’s term.

- End of Project:

- Final Evaluation: will take place three months prior to the final Project Board meeting and will be undertaken in accordance with UNDP and GEF guidance. The final evaluation will focus on the delivery of the project’s results as initially planned (and as corrected after the mid-term evaluation, if any such correction took place). The final evaluation will look at impact and sustainability of results, including the contribution to capacity development and the achievement of global environmental benefits/goals. The Terminal Evaluation should also provide recommendations for follow-up activities.

- Project Terminal Report: This comprehensive report will summarize the results achieved (objectives, outcomes, outputs), lessons learned, problems met and areas where results may not have been achieved. It will also lie out recommendations for any further steps that may need to be taken to ensure sustainability and replicability of the project’s results.

- Learning and Knowledge Sharing:

- Results from the project will be disseminated within and beyond the project intervention zone through existing information sharing networks and forums.

- The project will identify and participate, as relevant and appropriate, in scientific, policy-based and/or any other networks, which may be of benefit to project implementation though lessons learned. The project will identify, analyze, and share lessons learned that might be beneficial in the design and implementation of similar future projects.

- Finally, there will be a two-way flow of information between this project and other projects of a similar focus.